Venerable Khenpo Karten Rinpoche originally gave this teaching on June 3rd, 2011 at Wave Street Studios, where is was received by attendees in person and around the world as a live internet simulcast. Rinpoche requested that this teaching be shared with the Manjushri Dharma Center community again, and we are pleased to present it here.

I am delighted that we are going to have another session of Dharma teaching. I am particularly happy to know that there are many of my students in Malaysia, Singapore, perhaps in South Indian, and in Nepal; and in this country in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Portland who I have not seen for a long time—especially in Singapore and Malaysia. I know that many of you are seeing me and hearing my voice at this time, as well as friends and long acquaintances here. I am especially happy about that. Thank you to Wave Street Studios for making this possible. To all of you who are watching from elsewhere, I wish to say, Greetings and best wishes to all of you!

I want to give a brief explanation regarding sunyata—or emptiness. What are the causes of understanding it; and a brief explanation of it.

Although that is the main subject of my talk this evening, as I always mention: the preliminary stage is very important. In fact the preliminaries, actual practice, and dedication—all these three are important—but the preliminaries especially. It is said that the preliminaries are even more profound that the main teaching. There is something very important and profound about how we approach and set our intention for the teaching.

The great Nyingma master, Omniscient Longchen Rabjam, said that, “Indispensable to the attainment of omniscience are the three instructions of preparation, main body, and dedication. The motivation should be Bodhichitta, a very vast altruistic intention. Then that one should be undistracted from the actual nature of the main teaching. Then make a dedication prayer at the end. Without these three there is no way of taking the path to enlightenment.”

We have to check our own mind to think about, “Why am I here? Why have I come to attend to this?”

First of all, if the teacher was focused on a meal or some fame or renown, some kind of gain from the teaching, that would be completely inappropriate. For a listener also who was primarily focused on those things of this life, then the spiritual practice that is being done cannot in any way be pure.

I am giving a talk which is a part of the Mahayana great way teachings of the Buddha. But whether the teachings are Mahayana, that great way of Buddha or not, depends on the kind of motivation we set—whether it is great or not, whether it is Bodhichitta or not. The way to set that very vast motivation is to be here for the sake of all living beings, all life, all other living beings including oneself. Set one’s motivation by meditating now, thinking of the welfare of all these living beings throughout space, throughout the whole vastness of space. Think they are just like me, they want happiness, they do not want suffering. Why couldn’t they have happiness? Put that possibility in our mind. Why couldn’t all beings be happy? Wouldn’t that be wonderful, if all living beings could be happy? Then also feeling and thinking, “Well, I myself will undertake that. I will work towards that. I will serve that purpose of bringing happiness to all living beings throughout space. It is for this purpose that I am going to listen to the teachings and put them into them practice as best I can. Set this motivation.”

This setting of motivation is very important so I think it would be good to meditate on it for a short while, one minute.

<>><<>><<>

The setting of an altruistic motivation, when it is taken to its ultimate extent, is what we call Bodhichitta. The more altruistic we can make our intention the more it becomes Bodhichitta. This is the adjustment of our motivation at the beginning of the teaching. This Bodhichitta motivation is very precious, very sacred. As the Indian master, Bodhisattva Shantideva, says, in effect, “Developing Bodhichitta in your mind for even just an instant, whoever you are—whether an animal or human, or in the spirit realm—you become a child of Tathagata. You become a Bodhisattva. A child of the Buddha. One who is going to become a Buddha. You become worthy of homage by human beings and gods.”

Whoever develops that state of mind becomes worthy of homage, worthy of others’ veneration as someone who has great compassion.

All these infinite living beings have that wish to be free of pain, suffering, problems, and experience happiness, fulfillment, peace. We have only one method that can bring that about— and that is love and compassion.

Whether it is people killing each other on Earth in wars at the macro level or, at the micro level, people getting into arguments or fights with others, people hitting each other and so on; it all comes from this one problem: a lack of love, a lack of compassion.

Therefore, I want to talk about love and emptiness. Whether we are someone who accepts the existence of future lifetimes or not, these are qualities that can make us a more constructive better person. These are valuable to us whoever we are. Now to the main subject of emptiness—sunyata. Emptiness is a vast subject, a vast part of Buddhist teachings. The conduct in Buddhism is nonviolence. The view is interdependent origination. The view or philosophy of interdependent origination is really getting around to the subject of emptiness. This is because interdependency is the main reason behind emptiness. [Rinpoche laughs.]

In teaching emptiness there is nothing material to show, nothing to produce. So how do we talk about emptiness? It has to be based on experience. It has to be a sharing of experience. As far as my experience of emptiness goes—I have some, a very little. I’ll just be explaining a little of my experience, like an introduction pointing out the sights on a mountain. Just a brief introduction to that subject.

Emptiness is a little bit like talking about space. What if somebody asked you, “What is space? What is space like?” If you had to say, “Space is like this and that” it is rather difficult to explain—isn’t it? There is nothing, no color, no shape to describe if you are trying to describe space. Is it triangular, cubical, or spherical? You might have some other way to explain it. So emptiness is a matter of experience and understanding.

We can explain emptiness by inference and experience. Based on looking deeply we can discover or infer something through logic and through our experience. These are the tools we have for talking about it.

Even for someone who understands emptiness it is said to be very difficult to express. To take an example: what if there was a mute person and you gave them a sweet that they have never tasted before? They would be having an experience of something that is more delicious than anything they have ever tasted before. If you were to ask them, “What does that taste like? How sweet is it?” They of course cannot say anything. They cannot say a word about it. It is a bit like that. However, the experience is there. The mute person does know from having this experience that it is very sweet.

What is the cause for realizing emptiness? What is the cause of understanding emptiness?

The master Nagarjuna made a prayer saying, “Through the virtue created here may all beings create the two accumulations that lead to the form and truth bodies of a Buddha.”

The result of realizing emptiness is the creation of these two bodies of the Buddha—the form body that appears and can be seen and experienced by others, and the truth body, the mental body, the wisdom body. Those are the real fruition of understanding emptiness—attaining the bodies, the forms of a Buddha.

These two accumulations are called the contaminated, or relative, and the uncontaminated, or ultimate. Through the relative accumulation of merit, the form body of the Buddha is attained; whereas through the uncontaminated accumulation the body of transcendent wisdom, the deep awareness—the true body, the mental body of a Buddha is attained.

The relative collection, the collection on the material side is primarily done through physical and verbal actions, through physical homage like showing veneration to a master or a stupa by walking around them, ‘circumambulation’ it is called, or prostration or bowing and then saying mantras, saying prayers with the speech. Doing something that is called the “Seven Limb Prayer” These are the main kinds of practices through which one produces the accumulation of merit and one obtains the physical merit.

On the other side is the accumulation of transcendent wisdom accumulated through wisdom. It is this uncontaminated accumulation of transcendent wisdom that allows the attainment of the ‘Truth Body,’ the Dharmakaya of a Buddha. For attaining the mind of a Buddha, it is very important to accumulate the energy of wisdom unceasingly, to repeatedly meditate with wisdom.

The great Indian Mahasiddha Tilopa said to Naropa, “Until you become a fully-enlightened Buddha you must create the accumulation of merit unceasingly.” There is a need to continue creating positive energy with our body and speech all the way up to full enlightenment—to never separate from that.

By applying ourselves on these two levels, these two accumulations continuously with perseverance, after some time it will enable us to realize the true nature of our own mind. We come to encounter the deepest mode, the ultimate mode of existence of our own being.

Towards discovering and understanding our own true nature, our own deepest nature, which means to meditate on it, there are different types of meditation by which it can be approached: analytical meditation, or single pointed placement meditation.

Analytical meditation on emptiness is emphasized in the Gelug tradition in which there is a searching for the object projected by ignorance and then not finding it—realizing that it is not findable—and using logic and reasoning to do that, reasoning such as—if things are interdependent then they must be empty of independent existence. If things are empty, they must be interdependent. The Gelug tradition uses this kind of reasoning to approach and develop this experience. Whereas in the Kagyu and Nyingma, which is more my tradition, there is emphasis on placement meditation, a simple focusing on that deepest nature of our own being, of our own mind. There is more focus on the essence of our own mind—focusing directly on that without much analysis. Emphasizing the practice of not approving or rejecting thoughts, but placing the mind directly on the essence, that essential nature of the mind—that is the kind of meditation that is emphasized in our tradition.

When we look at the essence of our mind we are talking about not following after any thoughts of the past, nor looking forward to any occurrences in the future; but focusing on the very present moment of awareness. For instance, right now, I am talking to you and you are listening to me. That awareness of listening that is present in your mind this very moment. We are talking about focusing on essence. What is the essence of our present mind?

That essence of our mind is clear and aware and can never contain concepts.

If you are looking at that very present moment of the mind, delusions and afflicted states of mind are not possible. Yet we are constantly developing deluded states of mind. We do not see this essence of our own mind.

If we are asked, “Is there butter in milk?” we say, “Yes, there is butter in milk.” If we want to separate butter from the milk it takes churning it, shaking it, and eventually it will separate.

We can talk about a couple of different terms: mind and awareness. In this context they are differentiated. Mind has the quality of being deluded and impure whereas the term ‘awareness,’ here, ‘rigpa, in Tibetan, refers to this essence of our mind, this ‘rigpa’ awareness, this pure awareness—that we don’t see. In the midst of turbulence, afflictions, and impurities, we don’t realize it is there.

Regarding being able to separate pure awareness from afflicted awareness; one of Milarepa disciples asked him, “How do I meditate?”

Milarepa told the disciple, “Go—meditate like a mountain.”

The student went and meditated like a mountain—vast, stable, strong. But certain thoughts kept developing. In his experience, they seemed like trees growing on the mountain. The student went back to Milarepa and said, “Well, I can meditate on the mountain, but these trees are difficult. Please give me a away of clearing away the trees.”

Milarepa answered, “The trees are not a problem. They grow on the mountain. They will decompose into the mountain. There is not the slightest thought arising in your mind that is negative, that you need to get rid of. It dissolves by itself, back into your mind.”

Then he told the student, “Go meditate like the ocean.”

The student did that with vast motivation and, as so often happens, thoughts began to arise like waves on the ocean. The student went back to Milarepa and said, “It is easy to meditate on the ocean, but it is difficult to conquer the waves. How should I get over the waves?”

Milarepa gave him similar advice, “Those waves are just coming out of the ocean. They are the movement of the ocean. They are the manifestation of the ocean. They will go back into the ocean. Like that, these thoughts are manifestations of your deepest true nature that I am asking you to meditate on. They will dissolve back into it.”

After some time, Milarepa instructed the student, “Go mediate like the sky.”

The student was having a very vast meditation like the sky, like space. When thoughts started to arise, they seemed like clouds in the southern sky. The student returned to Milarepa and said, “It is easy to meditate on space, but difficult to get rid of the clouds in the southern sky. Please give me instruction to eliminate the clouds.”

Milarepa said, “Those cloud-like thoughts are not a problem. They arise in the sky of your mind. They will dissolve right there in your mind. Don’t think they are bad, just watch them come and go.”

Thoughts will come. When we try to meditate, there will be nothing but thoughts. [Rinpoche laughs.] When we use this method of looking directly at the essential nature of our own mind in the present moment we are using what could be called a remedy. When thoughts arise, it is important to recognize them as thoughts, to note that a thought has arisen. But when you look at its very nature it instantly dissolves. It does not remain. Eventually this is the kind of experience that occurs. It is called ‘simultaneous arising and release’ in the Dzogchen, Great Completion, teachings. It is similar to snowflakes falling on a hot sidewalk. Like in India, where it is very hot, if there is ever any snow it instantly melts as it hits the hot stone. It is like that with thoughts when they come into the environment of this kind of meditation—as soon as it is noticed that they have arisen they are instantly released and dissolve. In that way, you realize they do not have the essence that they seemed to have.

When we experience our true mind, our real mind, free of delusions and afflictions, it will be an inexpressible experience, like a mute person trying to describe tasting something sweet for the first time, having never tasted such a thing before.

As is said in the Praise to the Mother of Prajnaparamita, The Perfection of Wisdom, “Beyond speech, thought, expression, wisdom gone beyond. Unborn unceasing with a nature like space. Discerning transcendent wisdom’s sphere of awareness. Homage to the Mother of the three times Buddhas.” The phrase, “Wisdom’s sphere of awareness” means just that: it is in your own experience, your own awareness. That is the only place it is. It cannot be fully revealed outside of that.

Gampopa asked his guru Milarepa, “How shall I realize emptiness? What will it be like when I realize emptiness?”

Milarepa told him, “Don’t worry about that. You just keep working at it and eventually you will experience it. You persevere and eventually it will happen.” [Rinpoche laughs.] Milarepa told Gampopa, “When that happens, when you have that realization of emptiness, then you will feel great gratitude, thinking ‘Ah! That Milarepa is a real Buddha!’ And you will have compassion arising for all living beings in a genuine, unfabricated way. At that point, you will feel no need to work at it. It will be a spontaneous state of effortless knowing, I am a Buddha, and a spontaneous effortless compassion for all living beings, your mothers, throughout space.”

Now let’s take a moment for this meditation focusing on the essence of our awareness of this very moment—without me talking to you, or you listening to me—this present moment of awareness, the essence of our mind in this very moment.

<>><<>><<>

When we are beginners many thoughts arise very quickly in our minds, like mountain streams running down a mountain very fast, there is the movement of thoughts arising and becoming. The first thoughts come like a waterfall, so fast. If we practice meditation every day— I know there are beginners here, people just starting, young people—this kind of mediation, gradually extending the period of meditation, five, ten minutes and so on, eventually we will have fewer thoughts arising. It is more like water that has left the mountain and becomes like a meandering stream bubbling by; the thoughts slow down a bit. Eventually the water opens out into the great ocean. There will be a complete absence of thoughts. The thoughts have not been eliminated, per se; they have been transformed into transcendent wisdom.

This completes my brief explanation of emptiness. It is a very essential, sacred element of Buddha’s teachings, which I am especially happy to speak about because it creates a tremendous amount of positive energy. You listening to it creates a tremendous amount of positive energy ascending to the essence of Buddha’s teachings. Therefore, let us make a special dedication prayer together. I would like to take this moment to address my many students across the world. I have mentioned many students in different countries. Spain and Columbia are included among those. It has been a long time since I have been able to see you all, especially those of you in Singapore and Malaysia. We have been physically separated for a long time and if I had to call each of you on the phone it would be difficult. I want to take this opportunity now that I have all of you together to express special wishes. We may be physically separated but my mind is with you always. I want to say a special prayer for all of you. May masters and disciples be never separated, always together. May our lives be as long and as stable as the Earth. May our learning, contemplation, and meditation be unceasing. May all be auspicious for happiness and Dharma to flourish. Thank you everyone.

Click here to download teaching as PDF: Shunyata, Essence of Mind

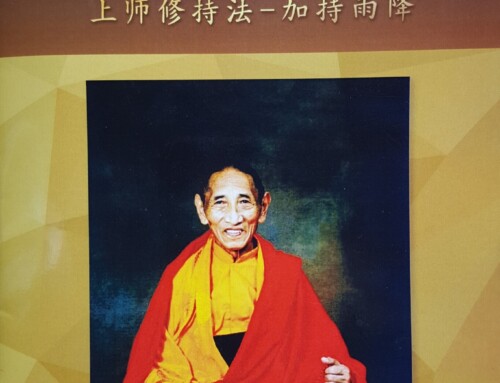

Venerable Khenpo Karten Rinpoche

Broadcast live at Wave Street Studios, June 3, 2011

Transcription by Jerry Hutchens

Interpretation and editing by Jampa Tharchi/David Molk